Professor of Literature, John L. Murphy presented the following paper to the American Conference for Irish Studies-Western Region. at the University of Montana, Missoula. 21st Oct. 2016. John L. Murphy runs Blogtrotter.

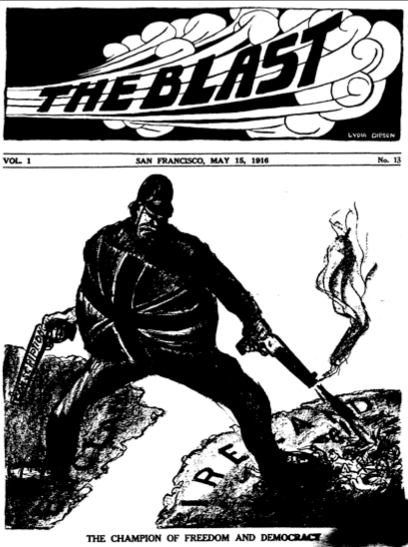

For twenty-nine issues, Alexander Berkman edited The Blast. This revolutionary labour bi-weekly opposed the Great War, capitalism, and colonialism. While “Sasha” Berkman’s companion Emma Goldman gains a greater share of commemoration, her fickle lover and devoted comrade merits attention as the Easter Rising and this paper’s centennial coincide.

Needing a break from “Red Emma’s” own Mother Earth, with its literary, intellectual, and theoretical bent, Sasha with Emma’s permission decamped from New York City to San Francisco to fire up The Blast as a politically incendiary publication. He began 1916 at 569 Dolores Street in the Mission District. There he and Mary Eleanor Fitzgerald, who had also worked for Mother Earth, set up the press and their domestic partnership. “Fitzi” had fallen in love with that Russian immigrant and notorious would-be assassin, after she left behind her Ohio upbringing as the daughter of an Irish Catholic emigrant and conscientious objector during the Civil War, and an Adventist mother from pioneer stock.

Together, Sasha and Fitzi entered a city no less calm than Manhattan when it came to unrest. San Francisco’s homegrown, Jewish, and especially Italian anarchists welcomed Berkman’s arrival, and fundraisers enabled The Blast to print. As its anthologist puts it, “social change was tantalisingly near.” As a Goldman-Berkman expert commends it: “A sense of absolute emergency pervades almost every column.” For its first sixteen issues, “McDevitt’s Book Omnorium” advertises “Radical Literature of All Kinds” at two locations, renting out “all sorts” at a nickel a week, and with “no censorship.” On November 12th 1916, “socialist teacher” William McDevitt alongside Berkman, war correspondent-cartoonist Robert Minor, and Mexican anarchist Ricardo Flores Magón would be slated among the orators on the 29th anniversary of eight Haymarket “martyrs.”

Such leftist lineups cheered The Blast’s launch. Introducing its debut, Berkman announces: “Blind rebellion stalks upon highway and byway. To fire it with the sparks of Hope, to kindle it with the light of vision, and to turn pale discontent into conscious social action–that is the crying problem of the hour.” This January 15th edition included Fenian felon turned journalist John Boyle O’Reilly’s poem conjuring up “spectres” of revolutionaries rising, a fitting portent for haunted months ahead.

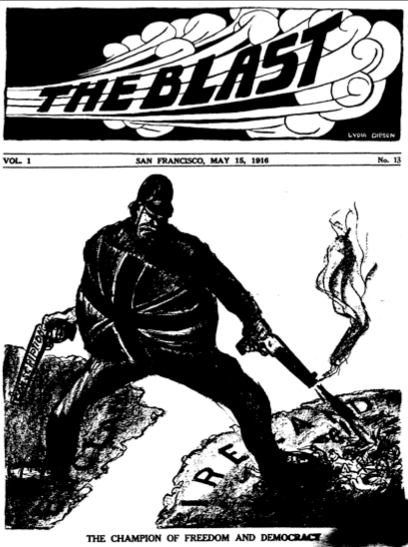

For its May Day issue offered unsigned “reflections” on “The Revolt in Ireland.” The Rising, as far as distant Californians surmised, was ongoing, although it had spanned the 24th to the 29th of April. The writer welcomed the rebellion, but reminded readers of the true enemy. Rather than England, “the Lords of Land and Life” loomed. Rather than a struggle for land and liberty, the nationalist character meant only a change of masters. “The club of an Irish Republican policeman upon a Dublin citizen’s head will hurt no less than the nightstick of an English bobby.” Better to lash out than stay passive, but freedom from “agrarian and industrial slavery” comes only, the columnist warned, from “making common cause with the disinherited of all countries, in a social revolution against the Universal Plunderbund whatever its international composition.” This heated, sassy style echoes Sasha’s even if it lacks a byline. After all, one of his pseudonyms for The Blast was “R.E. Bell.”

Page two presents Berkman’s fullest expression of the anarchist argument against the Rising’s target. “The Only Hope of Ireland” is absent from the compilation of Berkman’s many publications, and only surfaces on a few activist websites. Yet, it fuels a counter-blast to James Connolly’s prescient warning about switching the Union Jack but for a green flag over a capitalist-run Dublin Castle.

Why the surprise, Sasha asks, at the treatment of Sinn Féin’s rebels in the Irish American press? As in India, South Africa, and Egypt, so in Ireland. Colonial policy crushes, whether as Berkman cites under the British Raj, or against English workers. Conscription wields the clout of the ruling class. Whether kaiser, czar, or president, these foes comprise a cabal tainted by imperial greed. “Government is but the shadow the ruling class of a country casts upon the political life of a given nation.”

Make no mistake, this attempted murderer of Carnegie Steel’s anti-union manager Henry Clay Frick cautions: “the only safe rebel is a dead rebel” as far as the Crown cares. Beyond embittering the Irish people, the American Irish who protest collide with the Church and state which support Britain. To ensure the safekeeping of Sinn Féin captives in the motherland, her exiled discontents might pluck up hostages from among His Majesty’s representatives stationed in America.

Sasha suggests: “A British Consul ornamenting a lamp post in San Francisco or New York would quickly secure the attention of the British Lion.” Far more effective than petitions and rallies in Irish America, such strategies would hasten freedom for those imprisoned. Finally, Berkman blames “the Redmonds and the Carsons.” The pluralising of these surnames extends this anti-colonial critique to complicit politicians under Home Rule as well as Unionist perpetuation. Loyalist condemnation and Nationalist cowardice unite in alienating support for the uprising “in and out of Ireland,” as well as having “encouraged the English government to use the most drastic methods in opposing the revolt.”

Ireland’s labour leaders serve as lackeys for their landlords. As in “The Revolt in Ireland” two weeks before, “The Only Hope” concludes by urging the Irish to expand their radical aspirations beyond a clatter of weapons. Outside “the boundaries of the Emerald Isle,” Berkman assures, a global response to imperialism and for liberation will occur, one that erases all despots and opens all borders, at last.

The essay’s last sentence evokes imagery reminiscent of the Fenian sunburst flag. It recalls that mythic motif, unconsciously or not, while typifying the trumpeting tone of The Blast. True to the anarchist chant of neither god nor masters, the names of God and nation vanish from this tribute. Rejecting monster meetings or petitions for clemency, Berkman rallies to a cause that transcends any renegade tricolour.

The precious blood shed in the unsuccessful revolution will not have been in vain if the tears of their great tragedy will clarify the vision of the sons and daughters of Erin and make them see beyond the empty shell of national aspirations toward the rising sun of the international brotherhood of the exploited in all countries and climes combined in a solidaric struggle for emancipation from every form of slavery, political and economic.

Matching the Proclamation by appealing to the men and women of Ireland, it rises above the Republic’s territorial aspirations. Instead, The Blast praises global emancipation.

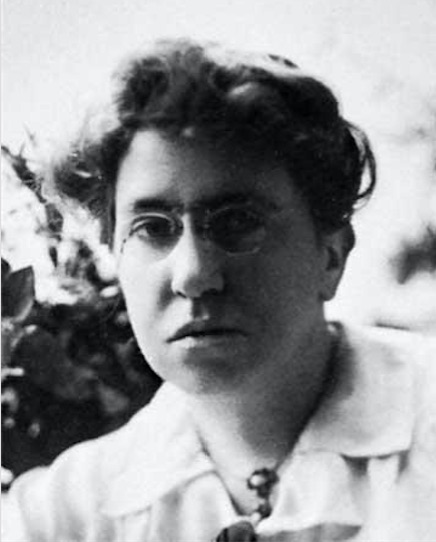

Alexander Berkman

For the next issue on June 1st, Emma Goldman, visiting Los Angeles, receives promotion for a week’s series of lectures at Burbank Hall. On the 13th, she spoke on “Art and Revolution: The Irish Uprising.” In July 15th”s “Preparedness for What?” Connolly elicited celebration within Edward Gammons’ anti-conscription piece, which encouraged readers: “Let us emulate the Irish rebels.” An editorial, “Vampires of Memory,” contrasts current clerical collections for widows and orphans of 1916’s dead with the Vatican’s prior condemnation of that rebellion and the indifference of the Catholic authorities to the “slaughter of Pearse, Connolly, and their comrades.”

These castigations faded, as another violent act attributed to Irish surnames erupted in a downtown far closer than Dublin. When July 22nd’s Preparedness Day parade in anticipation of entry into the war was bombed, ten San Franciscans died and forty were wounded. The authorities rounded up socialists and anarchists. Tom Mooney, the son of Irish immigrants, and IWW associate Warren Billings were arrested. The Blast found in their case, and those of other defendants, a home front cause célèbre.

During his strenuous efforts to fend off what was at first a death sentence for Mooney and Billings, later commuted to life imprisonment after considerable abuse within the police and judicial system, Sasha contributed to a collective statement in the August 15th issue, printed as a circular in 50,000 copies. “Down with the Anarchists!” includes Russian revolutionaries, Italian Republicans, Fenians and Sinn Féiners. These are not anarchists, however, but similarly desperate people, all “driven by desperate circumstances into this terrible form of revolt.”

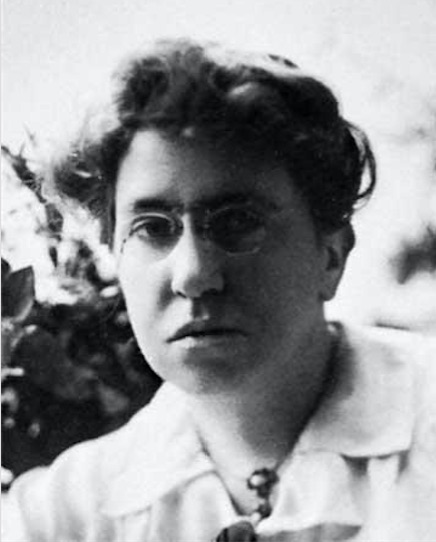

Emma Goldman

The writers follow Sasha and Emma’s attitude at that time to terrorism. They explain the “propaganda of the deed” as the last resort of those who have exhausted any hope of achieving their ideals by peaceful means. Berkman and Goldman ease off denunciation. This reply, as with the couple’s rejection of conscription, and Emma’s embrace of contraception, angered Federal authorities, who in 1919 deported both to Russia.

Meanwhile, the pair and their allies fought back. The night before the New Year 1917’s issue appeared, a private detective for the United Railroads and the Pacific Gas & Electric Company, accompanied by the Assistant District Attorney, and two of his detectives, raided the office of The Blast. Mary Eleanor Fitzgerald reported in “The Daylight Burglary” how vile their behavior compared to that of “Phadraig Pearse. Jim Connelly, Tom Clarke and the other gallant Irish rebels.” Within the raiders’ ranks numbered a Brennan and a Burke, she adds. Implicitly juxtaposing Hibernian heroes and touts here, Fitzi was also questioned after Preparedness Day along with Sasha the summer before that New Year’s Eve home invasion. In five hours of interrogation at police headquarters, she had to explain why “such a nice sweet lady with such a good Irish name” consorted with Sasha and his insurgent ilk.

Some still dispute the identity of the bombers, but the joint biographer of Berkman and Goldman points to San Francisco anti-militarist members of the Gruppo Anarchico Volonta. That scholar draws from deportation testimony of an Italian anarchist who denied Mooney bore any blame for the bombing. As the Red Scare threatened, the hunt quickened. Scattered mentions of Irish involvement in the movement speckle The Blast on February 15th. They mirror the sub rosa speculations, the whispers traded as Palmer Raids loomed. “Will You Be Man Enough to Come Forward?” reprints “speaking from memory” a note from a Clan na Gael initiate given to Jim Larkin after an address at San Francisco’s Dreamland Rink the year before on June 27th. This confides that the local police had framed Tom Mooney, Ed Nolan (a Machinist’s Union member) “and another, named Sheehan, a sailor.”

Communist organiser and American newcomer Jim Larkin’s seditious paper The Irish Warrior gains publicity in the same issue, as do Edward Gammons’ recollections of how Queen Victoria blocked Turkish aid to relieve the Famine, as despicable as British methods employed against its Indian subjects. Last of all, the humorist Finley Peter Dunne’s inimitable creation Mr. Dooley appears amidst the classifieds. “I’ll niver go down again to see sojers off to th’ war. But ye’ll see me at th’ depot whin th’ men that causes war starts fr’ th’ scene iv carnage.”

Roundups against supposed or real “Reds” accelerated after America entered the war in April. The trajectory of the fiery newspaper weakened after a May Day retreat to Emma and Harlem. Only five issues appeared in 1917, ending as June began. Irish concerns diminished as Berkman, Goldman, and 247 fellow-travelers with the far left faced forcible removal back to the countries of their birth. By the end of 1919, detained on Ellis Island, they were exiled from the America whose immigrants they had joined, and whose traditions they admired and challenged. Larkin, jailed in Sing Sing, would be pardoned, then deported, in 1923 by Al Smith.

Big Jim’s fate intersects with Irish rebels who escaped after the failed Rising to America, but who likely less often than Larkin and his like lashed out with such radical furor and fervent dissent against injustices they found in their second homeland and new refuge. Anarchism barely registered back in Ireland, amid red-baiting and moral panic. Reformist or conciliatory methods endured, as demonstrated by Larkin’s drift to the Labour Party in the Free State. Compromises characterised too the partitioned Irish Republic, testimony to class-based divisions on the island and beyond, past 2016.

Further reading:

Avrich, Paul, and Avrich, Karen. Sasha and Emma: The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman. Cambridge MA: The Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 2012.

Pateman, Barry, intro. The Blast. Edinburgh, London, Oakland: AK Press, 2005.

The Cruiser (as he was known) was a young liberal secularist whose first wife came from a Belfast Presbyterian republican family. Her father, Alec Foster, was a founder member of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association.

The Cruiser (as he was known) was a young liberal secularist whose first wife came from a Belfast Presbyterian republican family. Her father, Alec Foster, was a founder member of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association.